The sound of muffled bass is audible before you actually see the club. Tucked away down a series of alleyways in Parel – a downtown district in Mumbai, Maharashtra – from the outside antiSOCIAL looks like any other building in the Indian city: low-rise and slightly ramshackle, framed by palm trees. But inside its walls a musical revolution is in progress.

Socially conscious rap crew Swadesi are presenting their sold-out club night, Low End Therapy. Basking in the full force of the bass, the crowd is 15 people deep and everyone in the front row has their gun fingers out. BamBoy is behind the decks, DJing under his alias Kaali Duniya. The air conditioning does nothing to prevent the sweat dripping down his forehead as he plays his reggae and dubstep selections, whipping the crowd into a frenzy. They bounce on the spot and dance right up against the decks. A man with a broken wrist headbangs so hard he almost jogs the CDJs. Then BamBoy steps up to the mic and declares in Marathi, the state language, “The music you’re about to hear is called grime.”

BamBoy is often recognised on the streets of Mumbai these days. A few days before his club night, he’s stopped him midway through a mouthful of biryani by a young man in a Nas T-shirt: “Yo, BamBoy! I loved your Boiler Room set!” Last year, his crew Swadesi blew the world away with a live stream for the music broadcaster, showcasing 30 minutes of razor-sharp grime and hip hop rapped in Marathi, Bengali and Hindi, followed by a half-hour roadshow set from BamBoy alone. This was the first time that Mumbai street culture had been represented on the world stage, and the community adore him for it.

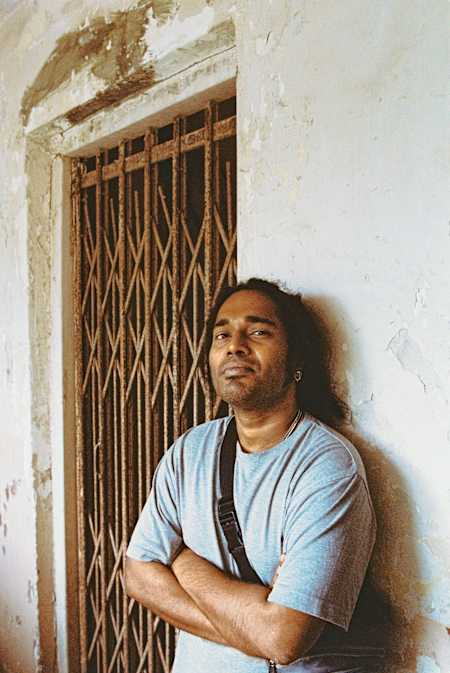

BamBoy, real name Tushar Adhav, stands about 5ft 6in (1.67m) tall but has the presence of a giant. He has intelligent eyes that miss nothing, and his customary dress code is baggy (“Not because of hip hop, but because I have a big belly,” he chuckles). BamBoy is a rapper and key figure in Swadesi, a group of multilingual, socially conscious rappers, producers and musicians who aren’t afraid of speaking truth to power. The crew formed in 2013 with the aim of addressing India’s many social issues and creating a community for those most marginalised, while also representing their own roots. As well as BamBoy, the collective comprised DJ/producer NaaR (Abhishek Menon), rappers MC Tod Fod (Dharmesh Parmar), MC Mawali (Aklesh Sutar) and Maharya (Yash Mahida), and DJ/producer RaaKshaS Sound (Abhishek Shindolkar). But Swadesi’s community is expansive, way beyond just the core members.

We really believe music can change the world.

Every few months, they host Low End Therapy to give lower-caste communities access to a club space and introduce them to reggae, dubstep and grime at a fraction of the usual cost. Swadesi’s members lacked the money to attend clubs while growing up, so Low End Therapy gives Mumbai’s low-income youth the entry point they never had.

BamBoy identifies as a member of the Ati-Shudra caste – the very bottom tier of India’s 3,000-year-old social hierarchy system – whose employment has traditionally been limited that of a labourer. “If you’re born into a lower-caste family, you die in a lower-caste family, even if you make millions,” he says.

In Mumbai, there’s wealth disparity everywhere you look. BamBoy was born and raised in Parel, not far from antiSOCIAL, where the city’s ultra-wealthy live next door to the impoverished. BamBoy was part of the latter community, the kind of kid who parents warned their own children about. “We were big into robberies and stuff like that,” he says. “We took gold to sell. When I was in the first year, I taught cuss words to the kids in the fifth year.”

It wasn’t school that eventually taught BamBoy the difference between right and wrong. “I got my education through music only,” he says. As a kid, the only access BamBoy had to culture was through roadshows – street parties with giant soundsystems that play local folk music and Bollywood remixes. His musical career began here as a soundboy, which led to him selecting warm-up music for the DJs. Then, when BamBoy was around 15, his best friend, MC Tod Fod, introduced him to US rap. “Most rappers talk about themselves,” BamBoy says, “but I was always inclined towards more informative rap that talks about culture and history, because that helped me understand them.”

Before Swadesi, club culture was run for and by rich kids.

Using his sister’s computer, he learnt how to produce music, spending entire nights making experimental hip hop. But everything changed the day he heard Wiley’s 2014 grime track Step 20. “I was like, ‘What lingo is this?’” he recalls. “I’d never heard UK English. I didn’t understand what he was saying. It was fascinating. Then I heard Skepta, and I started digging.”

In 2018, UK grime artist Flowdan came to India. “I was just blown away,” BamBoy says. “Such a big guy, big vocals, mashing up the place.” That year, BamBoy joined MC Tod Fod in Swadesi as a producer and began rapping himself. “And last year, when Flowdan came to Hyderabad, I opened for him,” he says with another chuckle. Last summer, BamBoy left India for the first time, with New Delhi-based radio station Boxout FM, to perform in London at British South Asian festival Dialled In. He followed this with a residency on online radio platform NTS. In January this year, he supported UK grime legend Killa P, who was so impressed with BamBoy’s skills they swapped places – the Brit DJed while his Indian counterpart rapped. “I didn’t know Mumbai had it like that,” Killa P said on the mic.

It’s extraordinarily difficult for those from lower-caste communities to break into the local music scene, let alone make a name on the international stage, and BamBoy’s achievements haven’t safeguarded him from experiencing prejudice on a daily basis. He says if he wasn’t working in the industry he might not be let into the clubs he plays at. “[It’s] because I don’t look rich and I don’t wear branded clothes,” he says. “If the bouncers are new, they think I’m there to pick up food deliveries.”

Swadesi’s members refer to one another as brothers, spouting in-jokes and often bursting into belly laughs before they can finish a sentence. These artists – most of them in their late twenties – grew up together, having met at either school, college or a now-closed café where rappers, breakdancers and musicians would hang out. Now, some of them work in call centres to make ends meet, and they all meet up most nights at one of several haunts in the areas where they live, Andheri East and Andheri West.

We decided that we didn’t want to stay quiet any more.

There’s a good view of Swadesi’s turf from MC Mawali’s roof. High-rise buildings loom over ramshackle shops as rickshaws and scooters zip through the streets, narrowly avoiding pedestrians. This scene is accompanied by Mumbai’s official soundtrack: the honk of horns, the sizzle of street food and the yell of street sellers. “I grew up on these streets,” Mawali says, gesturing to the city below. “I was outside all the time, 24/7, rap battling, B-boying, hanging out…”

The MC has a similar mullet to BamBoy’s and is dressed in baggy jeans and a T-shirt that depicts a Muslim and a Hindu woman kissing. Just like in BamBoy’s case, Mawali heard the messages in hip hop and applied his own life experiences to his rhymes. “I always wanted to release music that was powerful,” he explains.

Swadesi’s music is a series of rallying cries, rooted in protest.

This mindset unites the diverse members of Swadesi; theirs is a music rooted in protest. Popular tracks by the crew include 2019’s The Warli Revolt, a call-to-action opposing the destruction of Mumbai’s Aarey Forest; Kranti Havi (2020), their challenge to the discriminatory Citizenship Amendment Act; and Salaam (2021), an ode to India’s working classes. “The first song we released as Swadesi was Laaj Watte Kai, about a [widely reported 2012] gang-rape case in New Delhi,” Mawali says. “We decided that we didn’t want to stay quiet any more.”

Swadesi’s music is a series of rousing rallying cries that’s as much about education as it is entertainment. Representing distinctly Indian issues, their hip hop, dubstep and grime tracks counter the predictability of Bollywood pop, which remains the most accessible form of music for young people in India.

“We hope our music empowers, teaches and guides the youth of India and shows them what is wrong and right,” says rapper Maharya. He’s been penning rhymes – first in English, then in Hindi, then Bengali – since the age of 14, when he was introduced by his cousin to artists such as 50 Cent and Eminem. Maharya’s 2018 track Acche Din repurposed Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s tagline. “Acche Din means ‘good days are coming’,” Maharya says. “But nothing happens. The rich are getting richer, the poor are getting poorer. We want to raise young voices and show [Indian youth] how we use music as a medium to speak the truth.”

DJ and producer RaaKshaS Sound sees music as a form of therapy. “I make music for the people impacted by social issues and the inner turmoil that comes with that,” he says. His own music is full of tribal rhythms and sounds of everyday chaos from the streets – a recent track sampled road rage between two rickshaw drivers. RaaKshaS Sound has a limited set-up – just a laptop and headphones – even though he’s Swadesi’s official DJ. But despite often limited resources, he sees the Indian scene getting stronger. “There’s a growing community,” he says. “There are dubstep and grime producers in Bombay and Delhi now.”

Mumbai’s vast Aarey Forest is an unlikely base for a streetwise hip hop collective. But this is where Swadesi spend a lot of time together, out in nature, usually at a secluded spot by a lake. They share their love of the natural world with other like-minded people, too, organising regular Swadesi Treks through the area’s lush vegetation, as well as an annual festival – Swadesi Mela – deep in the forest, among the trees. Designed to get people out of the city, these events blur the conventional line between urban and rural: Swadesi take urban sounds out into nature and bring nature into their sound.

When working on The Warli Revolt, Mawali spent time with Adivasi people – the indigenous population of India – in their homes in the Aarey Forest, to understand the impact of development on their community. The song’s chorus, which samples the voice of Adivasi activist Prakash Bhoir pleading with the government to stop cutting down their trees, made a whole new audience aware of their plight.

“It’s time for the revolution to begin,” reads the text accompanying the video, which has more than two million views, on the Swadesi Movement YouTube channel. “Fight for the ones who don’t have a voice... Development is not destruction.”

Mawali has travelled to other parts of India to speak to village chiefs about the social and environmental problems they face and translate them into rap. He also teaches poetry and rap to schoolkids, and helps other crews get established. Mawali appreciates the power of well-crafted lyrics: “Poetry is supposed to shake you. It’s supposed to hurt your heart and penetrate your mind. We didn’t get taught this stuff at school, so we had to make it our own way.”

Music has been an important outlet for Swadesi’s own personal struggles, too. In 2022, the crew were deeply affected by the premature death of Swadesi linchpin MC Tod Fod, who suffered a heart attack on the last day of Swadesi Mela, aged just 24. They speak of him with affection and warm mockery, as if he’s still in the room. But beneath the smiles there’s still a lot of grief. “Life just stopped after that,” BamBoy says of his friend’s passing.

India’s fragmented, often expensive healthcare system has presented all these artists with their own concerns about medical welfare. Add to that the weight of economic insecurity. And daily prejudice. The whole crew are personally affected by so many of the issues they spotlight. What drives Swadesi is a vision of helping to create a better society through music. “We really believe music can change the world,” says Maharya. “Whatever we hear and see is what we can become.”

NaaR, regularly cited as India’s first grime producer, has been with Swadesi since they were a bunch of rap fans sitting in a café chatting about music and social issues more than a decade ago. He’s seen the change they’ve already made to Mumbai’s cultural landscape. “Before Swadesi, club culture was run by rich kids, for rich kids,” NaaR says. “We broke through that and made clubs understand that’s not gonna work. We have something else to offer.”

On the evening of Swadesi’s sold-out Low End Therapy night, the bouncers are under strict instructions to let everybody in, regardless of appearance, and by 9pm excited young people huddle outside. A man in skinny jeans and a Tupac T-shirt says he first heard Swadesi in 2018: “That’s when I decided to start rapping myself.” He points to his friend, a petite young man with very few teeth. “He’s a B-boy. He’ll do some moves for you later.”

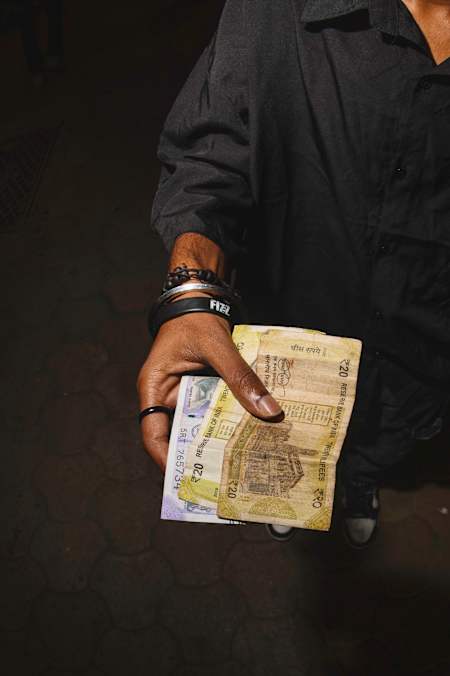

Tickets cost 140 Rupees (£1.40) to match grime and dubstep’s typical BPM. With most club nights charging 1,200 Rupees (£12), this makes Low End Therapy the most inclusive in Mumbai. For some here tonight, it’s a new experience, so when they enter and are greeted by NaaR playing grimy dubstep with bass so heavy it shakes the building, their faces split into grins. The crowd consists mostly of young Indian men, and some women too, plus a few foreign fans thanks to Swadesi’s Boiler Room set.

At 10pm, NaaR swaps places with RaaKshaS Sound. As his dubstep selections pound out of the speakers, the energy rises. Graphics proclaiming the club night’s name are projected onto the wall, lighting up dazed faces. As the music gets heavier, the crowd get happier, jumping up and down and crowding the speakers. Everyone knows what’s coming when Mawali, BamBoy and Maharya gather behind RaaKshaS to test the mics. “One-two, one-two,” BamBoy says. “Big up NaaR, big up RaaKshaS!”

We hope our music teaches and empowers India’s youth.

By now, there’s no empty space anywhere in the venue. RaaKshaS plays his dubstep track EgO Friendly and a small mosh pit forms. As his final track fades out, BamBoy steps in and plays an unreleased track, Annihilation of Caste, followed by a selection of his own reggae productions as Kaali Duniya. Then he steps up to the mic. “The music you’re about to hear is called grime.” An instrumental of JME and Skepta’s That’s Not Me bursts from the speakers. Mawali grabs the mic and starts spitting verses in Marathi to the frenzied audience. When he takes a breath, Maharya jumps in, somehow projecting complete calm while rapping at speed in Bengali. Then BamBoy drops in, drilling lyrics in Marathi and Hindi, headphones on, sweat dripping as the crowd wave, jump and scream.

When Swadesi close with The Warli Revolt, the crowd officially loses it, bellowing along, arms around each other, euphoric. This is the first time many of them have heard lyrics rapped in their own language, inside a club space. No wonder the response is volcanic.

What we see and hear is what we become.

After the show, the Swadesi crew gather on a rooftop. They lounge around on plastic chairs, laughing, sharing pizza, cracking jokes. Every now and again, one grabs another in a headlock. It’s the last night of Diwali, and fireworks light up the skies behind them – not that Swadesi approve: “They’re bad for the environment.”

The careers of this collective may be gathering momentum, their loyal following growing, their music taking some to new parts of India and others to new countries, but there’s no ego here. Swadesi is about the greater good and – before music or politics – friendship. They are one another’s future. Their dream is to own land in Maharashtra where they can build studio space to play music, produce, write, rap and throw Swadesi festivals. It’ll be a place free of judgment. Their own personal utopia that’s open to everyone.