Skydiving

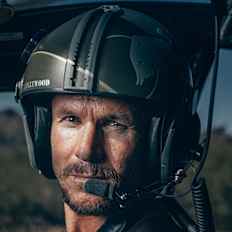

A decade on from Red Bull Stratos, Felix Baumgartner gives us the inside story of his historic space mission.

It was on October 14, 2012 that a then 43-year-old skydiver from Austria stepped out of a capsule on the edge of space, at an altitude of almost 40km, and began a free fall to Earth that made him the first human being to travel faster than the speed of sound outside a vehicle.

It took just 34 seconds for Felix Baumgartner to hit Mach 1, creating a sonic boom that could be heard by those watching from the New Mexico desert below and the millions around the world watching the mission live. After four minutes and 20 seconds, he opened his parachute and went on to achieve a clean landing.

A project more than five years in the making had gone almost perfectly. It was played out on 77 TV channels globally and the stream nearly broke YouTube servers. A decade on, content from Red Bull Stratos on YouTube has been watched close to a billion times and looking back, Baumgartner still sees it as a seismic moment. As he puts it in the new Space Jump documentary airing on Red Bull TV: “I was the first human being outside of an aircraft breaking the speed of sound and the history books. Nobody remembers the second one.”

At the inception of the project, Baumgartner, who had made his name crossing the English Channel with a carbon wing and with a series of world-record BASE jumps, first called engineer Art Thompson. The pair already knew each other, and Thompson had worked closely with Red Bull on a number of projects.

Baumgartner’s question was simple: “Is it possible to skydive from space or from the stratosphere and fall at supersonic speed?” Thompson said he’d have to think about it, but Baumgartner was never in doubt and Thompson soon bought into the dream with the words, “Let me find a solution!”

Part of the puzzle was who else to bring on board. Top of the wish list was Joe Kittinger, a former jetfighter pilot and the world record holder for a skydive having fallen from 102,800ft (31,333m) in the summer of 1960. Baumgartner's philosophy was simple: "If you want to climb Mount Everest and there’s only one guy on the planet who has been on top, you probably want to talk to the guy."

The pair traveled to Florida and Kittinger told them he would think about being involved if they treated it like an Air Force program with ground testing, low-altitude skydives and then high-altitude skydives. It was a philosophy shared by Baumgartner and Kittinger was quickly on board. It would be his voice that was the point of contact on the day of Baumgartner's own jump, going through the 43-point checklist before he exited the capsule.

I was the first human being outside of an aircraft breaking the speed of sound… Nobody remembers the second one

The team liked to talk about themselves as the underdogs and while the project group grew to around 300 people, an undertaking of such ambition was never going to be trouble-free. Looking back, Baumgartner likes to joke that any meeting would begin with trying to solve four problems and merely ended with finding four more. But the biggest stumbling block was arguably the pilot himself.

It's the freedom of flight that's always appealed to Baumgartner and on his arm is the tattoo ‘Born to Fly’. Inside the visor of his mission suit, he at first felt uncomfortable and eventually trapped. An hour was about his limit. On a day when a five-hour trial was planned, he was so affected he briefly walked away from the project. The answer was to bring in psychologist Dr Michael Gervais. Within two weeks, Baumgartner was able to spend hours on end in the suit. He wasn’t comfortable exactly, but he could do it.

Gervais helped to change his thinking with what he called combat breathing and put him in a number of uncomfortable situations, pushing him to the point of panic. When Baumgartner was struggling with the lack of control, Gervais reminded him he was the project’s hero, wearing a suit designed solely for him. It was then decided that Kittinger, the only man on the planet who could really understand what Baumgartner was experiencing, would be the sole voice of radio communication.

Training jumps from 13 miles (21km) and then 18 miles (29km) reassured the team that Baumgartner would be able to go through with the venture and, come October, everyone was ready.

The night before was understandably a sleepless one followed by an early call, and on the day itself, Felix squeezed into a capsule six feet (1.8m) in diameter, its flight into the atmosphere dictated by a thin helium balloon the size of 33 soccer fields.

The capsule in which he was sitting began as a wooden box with an office chair for the initial, rudimentary tests. By the time of the flight, it was a cutting-edge piece of tech, covered in 15 cameras, with a further five on Baumgartner’s spacesuit.

Looking back, he remembers having a love-hate relationship with the capsule and the suit, both in place to save his life. As he puts it, “If the suit malfunctions…you’re going to die. So, to have a double life-support system, capsule and suit cannot get better than that.”

As the key moment neared, Kittinger went through the meticulous check list, the two perfectionists on either end of the radio going through each and every feature that had been painstakingly prepared over so long.

A final list stood on the door he opened to begin his fall back down to Earth. Watching the footage live, the tension was palpable. Back at Mission Control in Roswell, New Mexico, those present remember a silence as he switched the pressure off in the capsule and on inside his suit.

As he stood at the capsule edge, his reported line of “I’m going home” is an apocryphal one. His actual message – “I’m coming home now” – got misconstrued by a brief breakdown in communications. He also uttered these fitting words: “I know the whole world is watching and I wish the whole world could see what I see. Sometimes you have to go really high up to understand how small you really are.”

Amid the intensity of the situation, he allowed himself to be aware of how peaceful and quiet his surroundings were. He nudged himself out, feet first and with as little movement as possible to avoid spiraling out of control.

Despite the steady exit, he would still perform one full revolution a second, fast enough to realize he needed to get it under control once hitting the thicker air. With barely any wind that high up, his skydiving skills were of limited use, yet he still managed to get the spin under control, although to this day he still does not quite know how that was achieved. It’s what he retrospectively calls “controlling the devil”.

Sometimes you have to go really high up to understand how small you really are

The objective of breaking the speed of sound had vanished from his mind. Half the scientists consulted had warned he would spin out of control, the other half that nothing would happen. As it transpired, it was somewhere in between.

After one minute and 20 seconds, he was at 62,000ft (18,900m) below the Armstrong line, where the blood boils without a pressurized suit. He was, as he puts it, “stable as a rock” and able to enjoy the experience. And the black sky was turning blue.

At 34,000ft (10,400m), the suit automatically depressurized. The final pivotal moments were for the parachute to open, which it did without fail with 9,000ft (2,750m) to go, and to open his visor and breathe in oxygen from the air around him once more. There was an overriding feeling of relief.

“I was very happy,” he recalls. “To me, working on Red Bull Stratos was like I'm in prison for so many years. And then finally, when my parachute opened on that day, I felt like those prison doors are open now again. And I can walk into the freedom because on all those vacations, all that downtime that we had, I was constantly thinking about Red Bull Stratos. You wake up with Red Bull Stratos, you inhale Red Bull Stratos, you go to bed with Red Bull Stratos. That’s why when I opened that visor... to me it was like a big relief.”

With the whole venture having gone nearly perfectly, he was then plagued by the thought of messing up his landing. “I really want a clean landing,” he recalls thinking. “Then I’m a happy person.”

It was picture perfect. He removed his visor after landing and hugged Thompson on the ground in jubilation before being whisked away in a helicopter back to Mission Control for further celebrations.

A party ensued and ended with him watching sunrise from the launch site, with another night’s sleep missed amid the adrenaline and euphoria. It was mission complete.

As Baumgartner recalls: “This was the first moment where I’m sitting there knowing I’m done. It was successful. Everyone is happy. I’m happy and I do not have to go back in the pressure suit anymore. No more testing, no more being occupied with Red Bull Stratos. So… I had my freedom back because all those years of preparation, I lost my freedom.”

In the aftermath, it felt like the whole world had been watching. He was one of the most recognized faces on the planet and it always seemed like he was being stopped by strangers – whether he was going to a restaurant or simply filling up his car at the petrol station.

Ten years on, he remains the man who fell from the edge of space – and can still make the whole experience feel like it was yesterday.