Skateboarding

Shaken with emotion, Steve Rodriguez stood in the Red Brick belly of the world's most famous skate spot. He cleared his throat, found his voice, then leaned forward and spoke into a mic to tell a joke.

“My last time at the Banks was so long ago—” he said, reaching into his pocket, “—that now I need glasses.” A laugh ran through the crowd, which included NYC major Eric Adams, numerous pro skaters, and Rodriguez’s son, Shiki.

All had gathered for the Brooklyn Banks’ re-opening, the result of a $160 million, two-decade effort that is now a monument to NYC skateboarding—a 50-year-old microculture once seen is being celebrated by the city that criminalized it.

Yes, times have changed.

“Evolution and innovation are at the core of skating,” Rodney Mullen told Red Bull. Known as “the Godfather of all modern skateboarding tricks,” Mullen has been a pioneering pro skater for 40 years, and is invented virtually every fundamental skate trick, including the flatground Ollie, kickflip, and 360 flip.

“Skateboarding will always change, and as this change happens, skaters will seek new terrain that let these changes manifest. There’s no better example of these evolutions than the history of New York City skate culture.”

Things sprouted in the ‘60s, a murky time in skate history—when 50 million skateboards were made in America—and a murkier time New York, since people remember skateboards but not an established skate culture. Roller skating seemed to rule the day, and skateboarders stayed in the shadows.

01

‘70s

This changed in the ‘70s, when the first tiny clusters of skaters appeared around the city, then converged in Central Park. By 1975, skateboarding was an established NYC counterculture—attitude and all. Descriptions from that time could match a skater’s experience today. There were spots, locals, and territories presided over by crews that didn’t like outsiders.

“Back then it was dicey,” says, JJ Veronis, who grew up in the ‘70s scene, and appears in Full Bleed, a best-selling book of NYC skate photography.

The scene’s epicenter was the Alice in Wonderland statue by East 74th Street. Skaters would gather, then disperse throughout the park and beyond, bombing hills by Tavern on the Green or at 9th Ave and 78th street, or—before security appeared—ride the brick transitions at Lax and 53rd or 89th and Madison (which remain today).

But most spots were DIY: short-lived and usually near construction sites, where plywood was accessible. In a dead-end 79th street alley, skaters built a multi-sheet plywood wallride, out of sight from authorities. A construction site at 96th and Riverside became a two-block succession of plywood ramps (graffiti taggers dubbed it “The Wall.”).

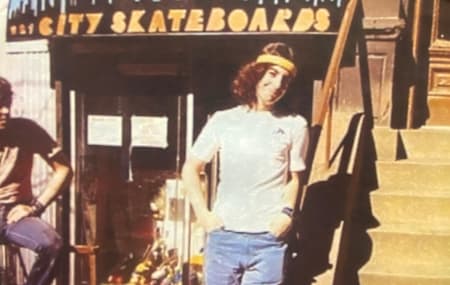

A very select few stores sold gear: A ski shop on 57th street sold boards. A stationary store on the Upper East Side kept pads and helmets in a single glass case. Paragon Sports in Union Square was reportedly the first to sell everything. In 1978, City Skateboards opened on East 83th Street—New York’s first real skate shop, run by Kevin Levine, father of local ripper Mark Levine.

New Lincoln High School at 70th and Lexington hosted what was probably New York’s first “official” contest; events included the “gorilla grip” highjump (just look it up).

A skatepark no one can name opened in Queens. And another in Riverdale. An empty pool off the last stop on the #1 line (242nd Street) was known as the Deathbowl.

“When you hit those, you went with a crew,” says Veronis, fondly, reiterating that ‘70s skate scene was less a sport and more like a branch of street culture: energized, dangerous, and “entangled” with drugs, live music, and especially graffiti. “Skating and graffiti were married.”

Perhaps this is why Andy Kessler remains the ‘70s central figure in NYC skateboarding.

A local pro, Kessler was a graffiti writer and member of the seminal upper west side crew, Soul Artists of Zoo York. Featured in Full Bleed and canonized when he died in 2009, Kessler best-represented skateboarding as street culture, in the ‘70s, a time that was already changing by 1979, when something happened in lower Manhattan.

02

‘80s

No one knows when the first skater rolled through Chinatown, crossed Pearl street, and started down the smooth brick basin that is now the most iconic skate spot in the world. It was probably 1979, the year “Red Brick Park” officially opened—a slim, block-long basin in this Lowest East Side neighborhood, complete with chess tables, a basketball court, and a tetherball station with no ball. “Kids would steal it,” says Rodriguez.

Indeed, this was not Central Park. What quickly became known as the Brooklyn Banks hosted as much a cultural template as a skateboarding. Skaters mixed with hustlers, homeless, crackheads, car jackers, graffiti artists (and sightings of Keith Haring and Basquiat)—who gathered here on public property that was removed from traffic, but definitely not a pedestrian or tourist destination, since there were no vendors or bathrooms.

What there were was transitions. Brick waves between the walls and floor. They ran the length of the park, starting at the northern end (small banks), where short brick hills abutted a low barrier separating the park from off-ramp traffic. Farther down, the banks grew, and were more like full transitions that grew into the Bridge’s huge vertical pillars (big banks).

Other spots and stores appeared around the city—a full-size, 12-foot half-pipe sprung up in Riverside Park, and downtown there was SoHo Skates, across from an abandoned gas station with a plywood wallride. But all paled in comparison, Rodriguez told Red Bull.

“By 1985, the Banks was the absolute epicenter of New York City skateboarding.”

This was the year the banks was canonized: First in Thrasher, then in Future Primitive, a film by Stacy Peralta, a ‘70s pro who created the iconic Bones Brigade skate team, and today is an award-winning documentarian. To film at the Banks, Peralta says, was both a nod to this new mecca and to this new genre: NYC skateboarding, that stood a world apart from its Southern California brethren.

“I wanted to show East Coast skaters that we respect them, that we believe in them, and that they have as much to offer as we do,” Peralta told Red Bull. “The history that took place on those walls—the evolution that happened there—it couldn’t be more important to skateboarding.”

The history Peralta mentions is key. It’s what made the Banks a skate mecca. The time—the 1980s—like the Banks itself, was unique in the history of skateboarding. No one could Ollie. Yet. Instead, skaters planted a foot and launched themselves, or sought ramps or transitions to leave the flat ground—making the Banks’ brick waves a worldwide skate destination.

Yet all the while, a young Florida prodigy (and future Bones Brigader) was adapting the trick to flat ground, emulating an elder pool rider, who could thrust his tail over the pool’s coped edge, catching a second of air. His name was Alan Gelfand, but everyone called him “Ollie.”

03

‘90s

The flat-ground Ollie—synonymous with 1990s skate culture—changed everything. Once airborne, skaters began flipping and spinning their boards—then taking tricks off-of and onto new surfaces.

“The possibilities were endless,” said Rob Rodriguez, a downtown ‘90s skater, who saw the NYC skate scene change and the Banks depopulate, as skaters sought new terrains.

“All of a sudden, it was about the street,” he said. “Curbs. Stairs. Planters. Hand rails.”

Rodriguez would later partner with Rodney Smith, founder of the seminal ‘90s urban company Zoo York—a nod to the iconic ‘70s crew.

[Away on a meditation retreat, Smith could not be reached for this article.]

Among other ‘90s skate companies, Zoo York used graffiti artists to make board and t-shirt graphics.

Some say this was the beginning of streetwear (a $300 billion industry today) and it makes sense, considering that in 1994, a tiny shop on Lafayette street that sold decks, hardware, and t-shirts screened with one word: SUPREME.

Local companies like Supreme, 5boro (est. 1996) and Zoo York illustrated ‘90s skate culture: tiny, urban, and independent. They boasted an urban, anti-skatepark (some argue anti-West Coast) ethos that enhanced its status as a branch of street culture. Seen in videos like Zoo York’s “Mixtape,” identity was forged thru music (hip-hop), fashion (streetwear), and of course the skating itself—which was now taking place throughout the city, with new gathering spots.

“Before 9/11, security was more lax, so you could session all these great places: Union Square. The Astor Cube. Times Square, especially at night. Oh, and Washington Square Park. That was the place.”

Washington Square Park was the ‘90s epicenter, and it’s no accident that a dark cult film synonymous with gritty NYC street culture was shot here. This was "Kids" (1995), starring iconic Supreme rider Harold Hunter and written by Harmony Korine, who met director Larry Clark while skating in Washington Square Park.

It’s worth noting that while street skating grew more inward and enriched, the ‘90s was also when skateboarding reached unseen popularity in 1995, when ESPN launched the X-Games, making Tony Hawk a household name.

The world seemed to be warming up to skateboarding, and eventually, so did New York City.

04

‘00s and Beyond

And eventually, so did New York City.

The 2000s saw the first official skateparks open in New York. McCarren Park (Brooklyn) to Rockaway Park (Queens) to River Ave Park, across from Yankee Stadium (Bronx).

And then Coleman Park, aka LES. The city installed some ramps and ledges circa 2005, but it wasn’t until a full redesign by Steve Rodriguez that LES became NYC’s new skate center. The park re-opened in 2012, three years after the Banks was abruptly shut down.

This was when Rodriguez first started working with the city, exercising more trust in authorities than any skater before him, even when the Banks were suddenly debricked in 2020, during Covid lockdown.

He points to Tony Hawk as a savior of the Banks, since it was Tony’s non-profit, The Skatepark Foundation, that helped make the Banks an official skateboarding site, finally.

Rodriguez and his son skate the LES park most Sundays, oft with other dads and sons.

But on May 26th, LES was curiously sparse. Skaters were at the Banks to see Steve Rodriguez usher in a new era—one where skate culture is not criminalized, but celebrated.

“The Banks has always been about community connectivity and the freedom of open public space for everyone,” Rodriguez said. “I’m excited for what’s to come.”